Through moments of unflinching, forsaken honesty and homespun grace, Sarah Jaffe carves an indelible impression on her recently released full-length debut, Suburban Nature.

In 2008 the Texan singer/songwriter released a six-song EP, Even Born Again, its stark and often Gothic-folk resonance laying the foundation of her sound. “The goal was to have it be a minimal introduction,” Jaffe says of the EP, “because at that point I was playing pretty much with just a cellist and, sometimes, another guitarist. So I wanted to stick to my guns and do what I did live.”

When it came time to record Suburban Nature, Jaffe maintained much the same objective while, at the same time, wanting to accent elements of what she describes as “outside ambience” in the production. As she recounts, “It all came together with adding extra layers and extra vocals, stacking vocals on top of each other and just moving about the room a little bit more.”

So does Suburban Nature stack up to what you hoped to make at the outset?

Absolutely. I’m really, really proud of it. The main goal was just to make an honest record. And I feel like that has been accomplished. So now that that’s happened I feel really good about playing these songs live. They’re just very true to what they are in themselves. I’m really happy about that whole presentation. There’s nothing in my mind that I’m doubtful of or questioning.

How is it translating live?

I’m working with a lot more people [now] and actually all are in other bands so I have this handful of people I work with, and they’re kind of interchangeable. When one’s out of town, another will play. And at some points they all play together. I’m playing with a cellist, a violinist, another guitarist, sometimes at least four string players, the keys who kind of fill in the ambience, and the drummer. So for the most part, all those parts from the record are being translated live.

How have you grown as a songwriter? Can you discern any difference or progression?

How have you grown as a songwriter? Can you discern any difference or progression?

The songs that I wrote on the EP, those were all new, actually [upon its release]. And the weird thing about the record is that the songs are literally from all over the place. The oldest song I wrote when I was 17 and the newest one was [written] two years ago. That was kind of interesting, going back and reworking those and not necessarily making them different melodically, but relaying the same emotion [and] backing it with a different take on that same emotion.

Is it difficult to relate to those songs given the newest ones are at least two years old?

Sometimes, yeah, definitely. Sometimes I will literally detach myself from a song and not even realize I’m singing, like I physically can’t hear it anymore. Then other times I’ll sing the exact same song and it makes sense all over again. The meanings are just constantly evolving for me.

As a songwriter, how do you take to the process?

I don’t write with any sort of strategy. I pretty much do it on impulse. That’s the way all of my songs have been written. They weren’t written with any preconceived thought. I mean, there may have been a prime emotion that was there in the beginning. For me it’s one solid emotion that I want to relay. I won’t sit down and not finish a song.

You won’t leave a song half done?

Oh no, I will never do that. I would much rather just not start at all than leave something like that. A lot of times I’ll have a certain idea poking around in my head for a while until it finally makes its way out, but…

Once you start, you keep going until it’s finished.

Absolutely.

Do you generally draw from your own experiences? Do you ever write from the standpoint of, say, a fiction writer creating altogether separate stories from what one sees or lives?

Do you generally draw from your own experiences? Do you ever write from the standpoint of, say, a fiction writer creating altogether separate stories from what one sees or lives?

I’ve always wanted to be someone who can write these elaborate stories that aren’t necessarily true, but I write from experience. I may embellish a little bit because, I think, [it’s] just my personality that maybe things are so much bigger in my head than they actually are. And so I’m able to embellish on them and make that emotion so huge, maybe bigger than it actually is. I can’t recall writing a song that wasn’t true or that didn’t draw from something that actually happened.

Do you ever fear giving too much of yourself away in your songs?

I would be lying if I said no. That is something that I do think about, but I think there are ways of being vulnerable without giving things away. I don’t think that would stop me from writing a song that felt right. All the songs, when I wrote them, felt true to what they were and I felt like I had accomplished what I wanted to say.

Suburban Nature is available now wherever quality music is sold. For more information on Sarah Jaffe, including details of an upcoming tour with fellow artist Lou Barlow that kicks off on June 10 in San Diego, please visit her official website.

(First published as An Interview with Sarah Jaffe on Blogcritics.)

“Writing is my absolute favorite thing to do,” Joan Armatrading says in no uncertain terms. “That’s the thing that I love.” It’s of little wonder, too, especially considering the breadth and diversities of her canon. For nearly forty years, the British singer, songwriter, and multi-instrumentalist has produced an eclectic string of hits — among them “Love And Affection,” “Willow,” “Drop The Pilot,” “Show Some Emotion,” “Kissin’ And A Huggin’” — forging a singular career that is as influential as it is renowned.

However, not even her most prestigious accolades — three Grammy® nominations (including a nomination for Best Blues Album, the first by a British female artist), the distinction of being the first British female artist to top the Billboard Blues charts (which she did for twelve consecutive weeks), and an MBE bestowed by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II — reflect the practical dimensions of her craft.

“A lot of the solos, for instance, I’ve literally only played them the once,” Armatrading says of her knack for nailing guitar parts on the first take. “Literally, the once. That’s it. Done.” Such was the case in recording “Heading Back To New York City” and “Best Dress On,” two of the standout, hard-driving tracks on her latest, decidedly rock-edged album, This Charming Life.

“It’s just what I feel like doing,” she says, explaining why she wrote This Charming Life within what she terms a “rock/pop” style, instead of exploring a range of genres as she has done in the past. “I’ve got to keep myself interested in what I’m doing.” No doubt her decision to perform just about every musical note on the album on her own kept her interested as well.

For the past several years you’ve taken to playing all instruments except drums on your albums. What does that bring to your music?

It’s actually something I’ve always done in terms of my demos. I’ve always played all the instruments myself on my demos. And when the musicians are here, they’re usually hearing the song with parts on it. So it was really just a matter of me deciding when did I do a record on my own like that? And I decided that I would do [2003’s] Lovers Speak like that. Having spent since 1972 to 2003 working with musicians, I think it’s all right for me to just indulge myself a bit and do it myself. It doesn’t mean I’m going to do it like that forever, but at the moment I’m really enjoying just doing it like that.

Do you discern a difference in how the music sounds?

Well of course it would sound different. If I said to one keyboard player, “Here’s a part. I want you to play it exactly like that.” And I said to another keyboard player, “Here’s a part. I want you to play it exactly like that.” Even though it’d be the same part — they would be playing exactly the same thing — they will sound different because they are two different people. That’s kind of how it works. If you said to ten keyboard players, “Go play me a C chord,” you’d get ten different-sounding C chords because they’re ten different people. That’s just the nature of that.

But I’ve always done my arrangements of my songs. So it’s not like something I’ve suddenly decided on, [that] I’m going to try to arrange my songs. From day one of making my records, since 1972, I’ve always been the person who knows what’s going to happen on my songs because that’s how I write. I write with the melody and the rhythm. And all these other things are, for me, a part of writing. It’s been like that ever since I started to write. So I’m very interested in parts…

And putting them all together.

Yeah. To me that’s the whole fun of writing. It’s the song, the whole song. So if I’m working with a producer or musicians, it’s not the producer or musicians who would dictate how my song goes. It would be me.

How do you approach the craft? Do you tell yourself, “I’m going to write a song about such-and-such,” or does the song, for lack of a better phrase, find you?

The song generally finds me. I have no idea how that happens, or why. I can’t tell you why somebody saying something or me seeing something or reading something, why that particular thing should spark up a song. I sometimes will take notes; I’ll write something down. I might not immediately go and write the song, but when the muse comes over me and says, “Okay, Joan, it’s time to write songs,” then it’ll either be from something that I’ve written before and want to write about and I’ve kept notes about. Or it could be about something that literally happened just that day or a couple of days ago. The process of writing, apart from saying I sit down at the piano or the guitar and it will sometimes be music first or words first or both together or from a riff… Apart from saying that I can’t really tell you how I get to writing a song.

It’s a mystery to a lot of songwriters.

It is a mystery. All I know is that when I write I like to have a beginning, middle and end to the song. I like it to have some kind of a flow and to have the words — if you took them out of context — make some kind of sense.

When you’re writing, are you trying to unearth the song like peeling an onion or —

It completely depends on the song. Some songs it really is as if you’re spinning something you know. It’s uncanny; some songs just flow out. Other songs take a little bit longer to write and work out. And some songs are just kind of in between. But they all dictate themselves. They’ve all got a life. There are songs you’d think, This would sound good on the piano, but you try to make it work on the piano and it just wouldn’t work. Then you try the guitar and instantly it’s a song. Or [it’s] the other way around. The songs kind of have a life of their own. I’ve heard people say this before, but certainly for me it’s true. They really do dictate how they want to go, what type of song, what tempo, the meaning of it, the expression of it. They seem to have their own thing that they want to do. And you just kind of have to follow them.

The other thing with writing, and it sounds really clever, but in actual fact half the time it’s just accidents. You go to play a D chord and your finger moves forward and suddenly instead of just a straight major you’re playing a diminished or a ninth or whatever just because you accidentally did that. The trick is to realize when you accidentally do something that you should keep it. That’s the part that you really need to be aware [of] because some people might think, “Oh, I really meant to play that D,” but if you’re not listening you’ll miss this little magical moment. And quite often that’s what it’s all about. It’s a series of accidents. [Laughs]

When you perform your earlier works live on stage, do you find as the years have progressed that the songs take on different meanings or yield new insights to you?

They do take on different things for all kinds of different reasons. They won’t stay exactly the same. “Love and Affection,” for instance, was 1976; it’s 2010. I was 26 then; I’m 59 now. If things were exactly the same, I’m afraid something would be not quite right just because I’m grown up. I’ve had many experiences, not just in terms of my life, but in terms of how I know people react to the song, what people expect from the song, their relationship with the song. All kinds of things come into play… How privileged am I that I can be still playing a song that I wrote in 1976 and people are reacting to in such a strong, strong, strong, positive way? How cool is that, that I’m able to sing that song and have that reaction? It’s fantastic!

In the liner notes of This Charming Life, you write that you’ve had a life-long fascination with music. As somebody who creates that which you’re fascinated by, what then keeps you fascinated?

It.

It?

Music. [Laughs] Music keeps me fascinated, because it’s an ever-changing thing. There are lots of different genres, lots of different emotions that you can get out of music. There are not that many chords, but what we can get out of not that many chords is quite remarkable. If you think about all these different kinds of songs, they’re really only coming out of a very small amount of notes. It amazes. And to try to work out what you can come up with that’s different and not similar to or the same as something else, just try to make that work, that’s quite an exciting challenge. As long as I’m fit and healthy and alive and alert, I’m definitely going to want to be writing.

For more information on Joan Armatrading, including tour dates in support of This Charming Life, please visit the artist’s official website.

Granted he’s not a teenage phenomenon anymore—he’ll turn 30 later this year—but Jonny Lang is still too damn young to be so damn good. On the opening night of his Live By Request tour, on which he includes a selection of cuts voted for by fans through his official website, Lang delivered an inspired performance. And in moments too frequent to mention, he sounded more like a seasoned bluesman from the Delta than a contemporary musician from North Dakota.

Variations of the blues indeed dominated early and throughout, as Lang began with a brooding version of “Give Me Up Again” before delivering “A Quitter Never Wins” with blistering fury and bite. Each solo elicited a flurry of grimaced expressions as if he were literally jolted by each chord he struck on his guitar. In other highlights, Lang steamrolled through “Still Rainin’” and “Red Light,” the latter’s urgent pace collapsing into a steady, rhythmic chant of “everything’s gonna be all right” that many in the crowd echoed with joy.

Closing out the main set with two covers, Lang not only underscored the scope of his influences, but—in pulling them off as well as he did—so too the depths of his talent. He dusted off an acoustic, guttural version of the Muddy Waters chestnut, “Forty Days and Forty Nights,” before ushering in a torrid rendition of “Livin’ For The City,” capping off the funky Stevie Wonder classic with a coda that spotlighted vocalist Jason Eskridge, whose soulful runs brought the concert to its climax.

Closing out the main set with two covers, Lang not only underscored the scope of his influences, but—in pulling them off as well as he did—so too the depths of his talent. He dusted off an acoustic, guttural version of the Muddy Waters chestnut, “Forty Days and Forty Nights,” before ushering in a torrid rendition of “Livin’ For The City,” capping off the funky Stevie Wonder classic with a coda that spotlighted vocalist Jason Eskridge, whose soulful runs brought the concert to its climax.

Some of the night’s extended jams ran far too long, though, particularly as they tended to feature everyone but Lang. The most unnecessary instance occurred on “I Am,” during which the star ceded the focus to each musician in the band, who offered up one ostentatious solo after another in what came across like a rivalrous exercise to entertain themselves rather than a collaborative effort to entertain the audience. More importantly, in the time it took to wind through all of this overindulgence, Lang could have played another one or two songs. On the whole, however, such criticism doesn't overshadow Lang’s contributions, which culminated time and again with stirring, genuinely soulful music.

—Photos by Donald Gibson

First published as Concert Review: Jonny Lang - Ruth Eckerd Hall, Clearwater, FL 5/21/10 on Blogcritics.

Among the most successful British bands of the past decade with over ten million albums sold, Keane have now added to their success, topping the UK Album Chart for the fourth time in as many releases with their latest, Night Train.

Diverse and genre defying, the collection reflects a bold creative shift for the trio—vocalist Tom Chaplin, pianist Tim Rice-Oxley, and drummer Richard Hughes—which is only magnified by Somali rapper K'naan and Japanese MC Tigarah making select appearances.

Despite it currently being the Number One album in the UK, at eight tracks Night Train is considered by the band as an EP. However, as Chaplin seems to suggest, in the course of broadening their sound, Keane may have unwittingly surpassed that intention.

Other than having eight songs instead of twelve or thirteen, what prevents Night Train from being Keane's fourth LP?

The way that we went about recording it wasn't really done in the conventional fashion. We started it with the intention of it just being a curiosity. We did a couple of songs with K’naan, and that was really all it was going to be. But we felt kind of buoyed up by that experience and, while we were on the road last year, we carried on. We had a mixture of different styles and different songs. It was something we just compiled as we went along in various different cities around the world. So it had this looseness in terms of the way it was made. And it turned from being what would've been sort of a single for the benefit of our hardcore fans to being something bigger. I don't think it ever felt like a full-album project. And I suppose conceptually we don't see it like that, but the way it's been received has almost kind of changed our outlook on it.

Perhaps people are responding to how eclectic it is, that you're exploring different avenues that maybe you hadn't as fully before.

It gave us a sense of real freedom. When you make an album, there's a conventional way of doing things—You get ensconced in a studio for several months. You make a record. You spend a few months promoting it. You go out on the road and tour it for a year. Then you go back in the studio. [Laughs]—that is cyclical. The nice thing about it was that it just came along and it was very loose and spontaneous. We didn't feel constrained by any kind of pressures or any desire to make it a proper album. Reversely, it really created this eclectic mix and that sense of total freedom. And so we’ve got a song like “Your Love,” which is Tim singing and very electro/poppy against a song like “My Shadow,” which is much more classic Keane, against a cover of a Yellow Magic Orchestra song [“Ishin Denshin (You've Got To Help Yourself)”]; and then there’s the stuff we did with K’naan. I don’t think we’d ever have considered that that was possible on an album, but kind of by accident we’ve ended up doing that.

Do you think it opens up a wider platform and more opportunities for Keane going forward to make LPs in this vein, where an album could be this eclectic?

Do you think it opens up a wider platform and more opportunities for Keane going forward to make LPs in this vein, where an album could be this eclectic?

The fact that this was such a kind of left turn has definitely been really informative and inspiring. I think it does give us the scope and the platform to do whatever we feel like. That’s pretty exciting to be in that position.

As on a song like “Stop For A Minute,” combining hip/hop with some of the sounds you’re known for making creates a whole new dynamic.

Absolutely. And I’m really glad about that. Some of our biggest heroes musically are people who aren’t afraid to jump from genre to genre. David Bowie is our spiritual hero in that respect. He is never afraid to try his hand at new things and different styles. That’s a great principle for working, not to feel like you’re confined by anything. There are plenty of British bands who come up with one way of doing things and never deviate from that path. We’d get bored if we ended up like that.

You’re still such a relatively young band to have had so much success. Going forward, to maintain your creative conviction and just your creative curiosity seems like a daunting proposition.

Yeah, which is why we embarked on a crazy project like Night Train. I think it’s good to remind yourselves of how different you can do things. We don’t want to stand still. It’s not in our vocabulary as a band. We just keep switching up and doing things different each time. I’m sure that the next record that we make will sound pretty different to the last one. There’s no great market plan with it. We just write songs in a certain way that seem to reach out to a lot of people. At the same time, we’re conscious of wanting to always progress and move in different directions.

Keane is touring the States toward the end of July. How do you regard the band’s reception here?

We’ve got a very dedicated fan base in America. We almost see our fan base in America like a family. It’s a very personal thing. We always try to take the opportunity to get outside and meet our fans after shows when we’re in the States. It just seems the right thing to do. I feel like our music is highly respected by our American fans and it’s not something we’d ever treat lightly; it’s something we’re very proud of and humbled by. I’ve got very fond memories of all the different cities that we’re getting to play on this coming tour. So it’ll be lovely to get back to each and every one of them.

For more information on Keane, including tour dates and locations, please visit the band's official website.

(First published as An Interview with Tom Chaplin of Keane on Blogcritics.)

You’d be forgiven if you mistook Future Sons & Daughters for a vintage reissue from some specialty label that houses obscure psychedelic, progressive, and bossa nova vinyl. With its laid-back, retro vibe and ethereal arrangements, the sophomore album by the artist who calls himself AM recalls some of the ’60s and ’70s’ most inventive pop.

“The sound of those records just really appeals to me,” AM says of that era’s music. “I’m sure a lot of it has to do with nostalgia, but I really do feel like that moment in time there was something a lot warmer and cozier.”

You’ve got eclectic taste in the music you make. Was that informed by your own discoveries growing up?

My parents had a pretty basic record collection growing up, but it was the good basics. But in terms of me, I just do a lot of digging. To me it’s the most enjoyable… I don’t know how to describe it. I guess it’s the same feeling a scientist gets when [he’s] in the lab messing around, that same kind of excitement and obsession. Just to start looking, find a record you like, and then put the pieces together and see what else that producer’s done or who else that artist has worked with and so on and so forth.

And friends are just essential. A good friend of mine who now lives in Brazil made me a bunch of records of other Brazilian stuff that I hadn’t heard. So had it not been for him, I wouldn’t have heard about this little segue. And I met this one guy many years ago whose dad once played with Sergio Mendes; he made a compilation for me of Brazilian music. To me it’s just a constant search and lately [I’ve discovered] a lot of Brazilian music, a lot of tropicalia, a lot of Italian soundtrack, a lot of Turkish psychedelia and folk — really just getting into what was happening around the globe in the ‘60s and ‘70s.

The Turkish had a psychedelic era?

Yeah, it’s amazing! Check out this artist, her name is Selda. There’s [also] a record label out there you should look into called Finders Keepers. They’re out of London and they reissue a bunch of really cool ‘60s and ‘70s psychedelic records.

What is it about the music of the ‘60s and ‘70s that resonates with you as much as it does?

The technology in terms of music came in and there were so many options all of a sudden. Recording technology had changed to where you could overdub and you could do more things so that really started opening up ground in terms of experimentation. And then, of course, The Beatles, showing everybody that artists can write their own songs, which we may have taken a little far these days. Because everyone thinks they can write a song.

Elvis Costello said in an interview once that just because you have access to a recording studio doesn’t mean you need to make a record.

Exactly. And back in the ‘60s and ‘70s that access was so hard to come by. You really had to prove yourself a lot of the time in order to get somebody to pay for you to go in and do that. It was an expensive thing and time was very scarce. You had to prove to people that you could write and perform before you stepped foot in there. Now people are just piecing it together and before they’ve even hit a stage they have a record done. It’s totally backwards.

How do you take to songwriting? Are you always thinking of ideas? Is it a struggle?

It’s not a struggle, but I’m definitely not one of those guys who walks around with music in his head all day. But what I’ve learned is that when you do get hit with an idea just to pay attention to it right then and there. So if I have a melody that comes into my head I immediately go and record it somehow. And I keep with that until I find that it sort of dies down. And if lyrics don’t happen on it right then and there, I’ll go back to it later when I have some more time to sit down with it and see what I’ve got. And what’s great is it’s almost like discovery too because I compile all these ideas and then I forget about them — I go on the road or something — and I go back to them and I forgot that I even did them. So when I hear them, a lot of times they’ll inspire, like “Oh, wow!” and from that I can build onto this and have this toying with this lyrical idea. So in a sense it’s all totally unorganized.

Once you get your ideas together, is it a discipline for you to then make sense of all that?

It’s fun and I really enjoy when I have the time to sit down and dig through things and write. And I’m the kind of person who needs deadlines. I like to tell myself, “If I’m going to make a record, I’m going to need to have some tunes done by this time.” Otherwise I’ll just tinker on it forever and never commit. I need sort of a deadline and that’s just how I’ve always been. You’ve got to decide. And if I don’t put a deadline on things, I just won’t decide. It’ll be like, “I could do this. Or I could do this. Or I could do that. Or I could do that.” That can go on… I also like being restricted in terms of instrumentation. I don’t want to have everything at my disposal to make a record. I want, “This is what I have. Let’s use these elements and make it sound the best we can.” Because if I have everything to choose from, then I’ll never decide. I hate having too many options.

How do you challenge yourself as a songwriter? Going forward, are there things that you want to do again and elements you don’t want to explore anymore?

What I’ve been listening to since I finished the record is definitely changing and that’s going to affect how I make another album. I’m definitely not into repeating myself. So I imagine there’ll be some elements of this album on the next album, but there’s going to be a whole new element of things introduced. I have some ideas. I want every record to be its own thing and have its own sound. That’s always a challenge, I think, for an artist. You want there to be some kind of consistency because hopefully that consistency is what keeps people liking your work. But you don’t want to bore your audience by giving them the same thing every time. I’d say the one for-sure quality that’s going to be there is groove. And that’s really all I can say.

For more information on AM, please visit the artist’s official website.

(First published at Blogcritics.)

Last year when Van Morrison revisited his classic album, Astral Weeks, in select performances across the country, he called to mind one of the most compelling instances in his canon in which the music was borne out of a conviction that even the most unintended note or inflection could yield altogether new inspiration.

In his new book, When That Rough God Goes Riding: Listening To Van Morrison, music critic and historian Greil Marcus examines this philosophy as it has manifested throughout the artist's career.

“It is at the heart of Morrison’s presence as a singer," Marcus asserts, "that when he lights on certain sounds, certain small moments inside a song…can then suggest whole territories, completed stories, indistinct ceremonies, far outside anything that can be literally traced in the compositions that carry them.” Marcus encapsulates that vocal capacity in a word—adopted from another Irish singer, the late tenor John McCormack, who intended it as a distinguishing vocal trait—which, in turn, informs his assessment.

There's a term you reference in the book, the “yarragh,” which seems to be an unreachable, intangible essence.

It’s definitely intangible; it’s not unreachable. Because if the book is about anything, it’s about those moments when he does reach that, and some times when he falls short that you can kind of see what he’s aiming at. I’m taking it to mean any moment in a piece of music where the performer breaks through the boundaries of ordinary communication. And you just said something about essence, and that’s really it. You reach a point where you are getting across emotional depth and intensity and completeness that in many cases goes beyond words, any ordinary words, but goes beyond vocal sounds too.

You write that Morrison is on a quest, one that’s “about a deepening of a style, the continuing task of constructing musical situations in which his voice can rise to its own form.” That leaves the audience—whether one listening to an album or live in concert—out of the equation, doesn’t it? If he’s just up against himself…

Well, in that sentence, sure. Except if it’s about communication, if it’s about breaking the boundaries of communication, you have to have someone to communicate to. And that’s not yourself.

In the context of his live performances, you touch on how Morrison can be diffident and aloof with his audiences, yet resonate so profoundly with them.

I think it really is about sound, the kind of sounds that he can, or on a given night, can’t, generate. And so often that’s a matter of momentum, musical momentum, rhythmic momentum, and emotional momentum. I think I have a line in the book where…I’m thinking through him, as if he were saying, “Just because I have these songs I want to perform doesn’t mean there has to be people here to listen to them.” I’ve done one reading for this book and I learned a lot from the audience that night. One person talked about a night he had gone to see Van Morrison, and after the show he went to a bar and there were a lot of people at the bar who had been to the show. And after a certain point Van Morrison came in and people stood up and they cheered. He sort of didn’t really acknowledge that. And the guy who was telling the story said that he finally worked up his nerve and he went over to Van Morrison to try and tell him how much his music meant to him and how glad he was that he’d been able to be at the show that night. Morrison turned to him and said, “Why is it that people feel the need to tell me these things?” Why does the audience have to exist at all? [Laughs]

There’s a documentary, From A Whisper To A Scream, about the history of Irish music in which Van Morrison is interviewed on Astral Weeks. While other subjects in the film praise it, Morrison acts like it was just another album: He went to work, made a record, and moved on to something else.

No performer, or no person who does creative work whether it’s a novelist or a singer or film director, actor, wants to be the prisoner of his or her past work. Otherwise you can’t go to anything new with a sense that is new, that you’re going to do something you haven’t done before, [that] you’re going to break through into an area you’ve never been able to reach before. I would think that would be both incredibly tiresome for Van Morrison to always have people tell him, “I love Astral Weeks so much,” or whatever it might be. And then he might say or he might imagine, “Well, did you hear The Healing Game or did you listen to Keep It Simple?” “Oh no, man, I stopped buying records back in 1981.” That’s awful.

But music occupies a certain nostalgic position in people’s lives. If you hear a Beatles song or a Rolling Stones song from the ‘60s, that triggers a memory in your mind.

Well, I don’t know. I’m not sure it really works that way. God, no one is more nostalgic than Van Morrison. No one takes nostalgia for childhood, for being a teenager or being the kind of teenager maybe he never really was, but would’ve liked to imagine he could have been—

You think he looks back like that?

You think he looks back like that?

He very explicitly looks back. Over the last twenty, twenty-five years in song after song after song [he’s made] nostalgia really the centerpiece in terms both of melodies and rhythm and words of his music. And yet, I think it’s always to get somewhere, to get to the childhood [you] didn’t live; to see the things you didn’t see then; to do the things you didn’t get to do then that you only wished you could. I mean, when you listen to “Behind The Ritual,” which is on his last album of new songs [Keep It Simple], it starts out as simple and kind of puerile nostalgia and it becomes something so much richer.

When I hear something that's really powered by its own engine [and not] by whatever associations I might bring to it—say, "Gimme Shelter" by the Rolling Stones, which I hear on the radio every few days and I feel like I have heard it on the radio every few days since it came out—it's like I'm hearing it for the first time. And I'm noticing things I never noticed or some aspect of the song seems primary where before it seemed just like decoration. I don't think it has anything to do with nostalgia. I think it's about somebody responding to something and becoming more of a person because of that experience. When one's reaction is nostalgic or if it triggers a memory or some past association, that reduces whatever it is you're responding to to something like looking in a scrapbook or your old high school yearbook.

Like associating a song with your first car.

Yeah, whereas we're talking about art. We're talking about the way art moves people and upsets people, makes them feel fulfilled and glad to be alive or whatever it might do. Which means that it can never really be controlled. It can never really be fixed. And I think Van Morrison has made so much unstable music that that kind of thing can happen in so many different places in any stage of his career.

Having attended Morrison’s Astral Weeks concert in Berkley, were you compelled to measure the performance to the album? Or did you just take it for a concert?

No, what I wanted was for the songs to come alive in a way that they didn't on the album, [to] take a different shape. In other words, to play these songs as opposed to playing the album. And they played the album. So it was a replication, really, or as close as they could come. There weren't any moments of surprise or spontaneity. And in that sense it was really disappointing… I saw him in early '69 in San Francisco at the Avalon Ballroom. He was playing with just two other musicians, a bass player and a flute and saxophone player. He did all of Astral Weeks that night, not the order of the songs they appeared in, which he didn't do last year either. And there wasn't any question that he was still lost in that music. It was not a closed book to him at all. I remember that in some ways more vividly than the show just last year.

Given how you describe Morrison in the book, do you see any comparable artist? The one that comes to mind is Neil Young.

Neil Young is probably the best analogy. I think that's really on the mark. Not that they're identical or maybe even that similar, but... There's a moment on "Over and Over" on Ragged Glory where something absolutely extraordinary happens in the middle of the instrumental break. The only way I've ever been able to describe it to myself is that the song turns over. I've only heard that one other time, in one other piece of music. So I don't think it's something anybody can aim for or really replicate. And if you listen to the Dead Man soundtrack that Neil Young did, which is just him playing guitar, I think you can hear that same sense of trust in the music or in your own ability to find it, but also the willingness to just go out there, poking around in the bushes for days if that's what it takes to find what you're looking for. I love something Neil Young said in the '90s, and he was being interviewed on the radio about grunge. And he said something like, "Ya know, all those old guys who play guitar, they don't know what grunge is." And I'm thinking, All those old guys? [Laughs]

Like Eddie Vedder?

I don't know what he meant—Neil Young at that time was one of the old guys—but he was saying, "All these old guys, they don't know what this is. They don't understand it. When you play that kind of music, there's no feeling like it anywhere." And he's saying, "I play this music in order to feel myself emotionally respond to the sounds that I'm creating. I'm my own listener." What a wonderful thing. Now whether Van Morrison is his own listener in the same way, probably not. But they're both people who can be enormously frustrating in terms of making tiresome music, making albums that you never want to listen all the way through let alone ever play again, but that you can't ever write off. You have no idea what they're going to come up with.

Of the general observation you make in the book, that there are elements at work in Morrison’s music that aren't necessarily charted note for note—that some things just happen—do you think he perceives what he does as having that much to do with chance? Because he's extremely talented.

I can't speak for him. I did find something he said in an interview very revelatory where he said something like, "The only time I'm really concentrating on the words is when I am writing them. But after that, when it comes time to sing the song, I release the words. And the words go out and they do what they want. Sometimes it's me chasing them or it's not up to me how they are going to arrange themselves." So if it's not exactly chance—and God knows there are enough horn arrangements in his music. There are arrangements. There are charts. They've been structured. They've been given to the musicians—then it is an openness to surprise, to spontaneity, to letting a piece of music go somewhere that you didn't intend. I've always been interested in music as event, as the record is something that actually happened as opposed to something that you really could do seventeen takes on and most people wouldn't notice the difference between them but the musicians can tell when one's a little better than the other.

I always think of the Rolling Stones' "Going Home," which is on Aftermath. The story always was that they had this song called "Going Home" and the first two-and-a-half minutes or so are Mick Jagger singing about going home. It's actually kind of dull. Then at the point where the song would be faded out, somebody finds something interesting in the rhythm and keeps playing. And they start to fool around with the rhythm. And the story was Charlie Watts, knowing that the song was over, got up from behind his drum kit and started walking out of the studio while everybody else was still playing. And somebody yelled at him, "Get back there!" I don't know if that story's true or not, but I love the story. And of course they go on for another, what is it, nine minutes or something like that in one of the most extraordinary things they ever did, and something they never have been able to or maybe never even tried [again]. They didn’t record it again; they've never played it live. It was something that happened. It was when they discovered themselves as musicians. Now that kind of event for the Rolling Stones is very unusual. For Van Morrison, you hear that kind of event all through his music, over and over and over.

How much credence do you give to Morrison’s talent, though, as opposed to something magical that happens? There has to be a baseline of talent to even have the possibility for magic to happen.

Well, I think his talent, at its deepest, is for opening up a feel where magic can happen. That's his talent. People who don't have any special talent, who really do just go through the motions or who have developed a product that market-research surveys have shown people will buy over the long term—and a lot of bands and a lot of performers really do work that way—don't have that kind of talent. Most of us probably don't. But I think he does.

When That Rough God Goes Riding: Listening To Van Morrison by Greil Marcus is published by Public Affairs™, a member of the Perseus Books Group, 2010.

When That Rough God Goes Riding: Listening To Van Morrison by Greil Marcus is published by Public Affairs™, a member of the Perseus Books Group, 2010.

Greil Marcus photo credit: Thierry Arditti, Paris

Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers are gearing up for their much-anticipated summer tour in support of Mojo, the band’s first album since their 2002 concept album, The Last DJ.

While the new LP doesn’t hit stores until June 15, those who purchase a ticket for the tour online (or who already have) can download a copy on its release date at no additional cost. Two tracks—“First Flash of Freedom” and “Good Enough”—are available immediately upon purchasing a ticket. Also as part of the deal, online ticket buyers will be able to download a batch of live performances culled from select dates once the tour wraps.

Much as he did on his last road trip in 2008, Petty has recruited a roster of classic and contemporary artists to open, including Joe Cocker, My Morning Jacket, Buddy Guy, Drive-By Truckers, and Crosby, Stills, and Nash. The tour kicks off on June 1 with a two-night stand at Red Rocks Amphitheatre in Denver, but Petty & The Heartbreakers will warm up with an appearance on the May 15th season finale of Saturday Night Live.

Anyone who’s witnessed Jonny Lang in concert already knows of the febrile passion he summons on stage. Often looking as if he’s locked in his own zone, galvanized by an electric guitar, the once-child prodigy and now-29-year-old seasoned musician elicits many an inspired, spontaneous moment rather than merely duplicating his songs in front of an audience. Which is arguably why his studio albums have never really been able to capture that same impulsive energy.

That’s not to say his records, particularly his lauded major-label debut, Lie To Me, and his even more realized follow-up, Wander This World, didn't offer soulful, formidable performances. However, the difference between the LTM version of “A Quitter Never Wins” and the one on his latest release, Live At The Ryman, is pronounced.

It’s much the same story throughout as Lang delivers a solid if not altogether well-rounded batch of songs—nearly half come from his 2006 Christian-influenced LP, Turn Around—leaning heavily toward more-recent fare. Still, he shines on “Give Me Up Again,” exhibiting his vocal maturation as he sings with marked restraint before and after howling out its anguished refrain. Things then simmer down on “Breakin’ Me,” with Lang drawing out the poignant, acoustic cut for nearly eight minutes.

Despite boasting a funky roll through the Prince-penned cut, “I Am”—which Lang wraps up with some high-pitched wails that would make the Purple One proud, or jealous—the album’s major disappointment is in its overall shortage of covers. In fact, Lang often dusts a few of them off during his concerts, including Stevie Wonder’s “Living For The City” and “Superstition,” his take on the latter bearing striking resemblance to the late Stevie Ray Vaughan’s ferocious rendition. Such inclusion would not only have been welcome, but it would have also reflected more of a representative set overall. Nevertheless, Live At The Ryman is sufficient in its merits to please old and new listeners alike.

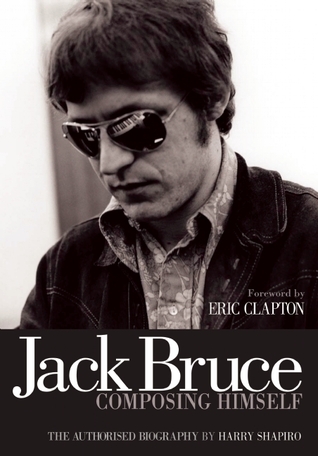

Five years ago this week, Cream reunited in a four-night stand at London’s Royal Albert Hall, heralding the first time that Jack Bruce, Eric Clapton, and Ginger Baker had performed full concerts together—and apart from their three-song set at their 1993 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction, the only time to date—in nearly forty years.

The unlikelihood of this monumental happening, widely considered among the most anticipated reunions in rock history, was staggering on many levels. For Jack Bruce in particular, though, such a feat was nothing short of extraordinary.

Authorized by and in collaboration with the music legend, Jack Bruce: Composing Himself offers a riveting portrait of a life lived in near-constant, creative pursuit. And while his fleeting, two-year tenure in Cream no doubt overshadows what has otherwise been an extensive and incomparable career, its lineage—from his earliest days as a member of the Graham Bond Organization and Manfred Mann as well as his later stints with Robin Trower and West, Bruce, and Laing—is chronicled with encyclopedic depth and striking, often-poignant retrospection. As author Harry Shapiro eloquently suggests, the music of Jack Bruce—and for that matter, the circumstances both triumphant and tragic that have informed it—is one well worth appreciating.

As you mention in the book, this is the first biography you’ve written in collaboration with the subject. Was it difficult to get Jack Bruce to be a part of it?

No, no. Quite the reverse. It took me by surprise, really. I sent him an email back in the summer of ’07 and said, “You know, I really think it’s about time there was a decent book about your life and career.” And back came an email, almost straight away, saying… What he actually said was, “I thought you’d never ask,” which was quite flattering. And away we went. It was no struggle at all to get his involvement.

Was he ever reluctant about addressing any significant aspect or event in his career or life?

No. He was pretty candid about most things. The one area which he was understandably a bit reticent about was talking about his son, Jo, who died of an asthma attack in 1997. That was really too painful and I really didn’t want to press him too much on that. On one level, of course, what can you say? It’s a terrible tragedy, it came out of the blue, and that was that. But I really didn’t want to delve too deeply into that. That aside, he was pretty candid about most aspects of his life, I have to say.

In the acknowledgment section of the book, you thank a list of people—some familiar names, others not so familiar to music fans, but pertinent to the biography—and Eric Clapton is mentioned, [lyricist] Pete Brown is mentioned. Ginger Baker is not.

[Laughs] I did ask him. Right at the start I asked him if he would be prepared to be interviewed. And he very politely emailed me back and said that he would rather not get involved. And I can quite understand that, in a way. And to be honest, pretty much what Ginger would say to questions like that was already on the public record. His longstanding sense of injustice about Cream and things like that has all been documented.

Royalties?

Yeah, all that kind of thing. And there were lots of stories about various incidents that happened in which Ginger may well have disagreed with anyway, but ultimately it was Jack’s story. So I can’t say I was that surprised when he declined. Like I say, much of what I imagine he would have said was already on the public record. And also, I got some interesting insights from Ginger’s family, his wife and his daughter, Nettie.

Jack and Ginger, from early ages through recent years, have had a love/hate relationship yet they still come together to play.

Jack and Ginger, from early ages through recent years, have had a love/hate relationship yet they still come together to play.

Indeed, yes, that’s very interesting. It’s funny, Eric said to me for the book that—he was talking about Cream, but I think it runs all the way through—they play so well together, they’ve got such an instinctive feel for each other as musicians, once they kind of lock together it’s very hard for anybody else to come between them in a kind of musical way. Jack is always very complimentary about Ginger’s drumming. Ginger doesn’t reciprocate, I have to say. But Jack’s always said, “What a great drummer. He’s one of the best ever.”

In the book, he says Ginger’s the best rock drummer ever.

Yeah, and it’s always Jack who’s kind of brought Ginger in on the bands that [he’s] been involved in, the [Jack Bruce] Band in ’89 and BBM in ’94. So Jack’s always been wanting to get Ginger involved. And people have often looked a bit askance when he’s said, “Let’s get Ginger in,” and people go, “Well, isn’t that going to be a problem?” Jack genuinely feels that it won’t be, but quite often it actually turns out that it is. But it doesn’t stop Jack [from] wanting to play with Ginger. And Ginger doesn’t say no.

Going back to Jack’s early musical career—up through to Manfred Mann—he seemed as motivated by money as he was music. He almost looked at each endeavor like a tradesman, like a plumber or a window cleaner looking for a job. There didn’t seem to be much glamour.

The first thing was he was a professional, working musician. That was his job. One can’t be too romantic about it. This is what all these guys were trying to do—John Mayall, Peter Green, Eric, Ginger, all of them were working musicians. They did hundreds of gigs a year up and down the UK in these rickety old vans, terrible conditions, trying to earn a few dollars a night. So there really was nothing glamorous about the whole thing.

The other thing is that Jack did get involved in a number of more avant-garde jazz things with Group Sounds Five and Mike Taylor Trio, for which he probably got no money at all. But on the fringes of the London jazz scene—when he was able to not play with, for example, Manfred Mann, going up there for a half hour every night and playing Manfred’s hits; he soon got bored doing that but he still got paid—being able to sort of stretch out and improvise with other jazz musicians in small jazz clubs, he was equally keen to do that as well. So it was all about playing, it was all about trying to earn some money just to live, because there was no other income coming in. There was no record royalties or anything like that. Most of the money these guys made was from playing as many gigs as they could fit into the course of a year.

It seems like such a blue-collar approach.

But he wasn’t alone in that. That’s the point I’m trying to make, that all these guys were out there trying to learn a craft, doing what they loved doing. I mean, they could’ve gone off and become builders or plumbers or electricians, but they were musicians. And they knew that it was going to be a struggle. They had to play an awful lot in order to get any kind of decent living.

In talking to him, did you sense any regret or sadness that he’s had such longevity in his career, but most people only equate him with a band he was with for two years?

I think he’s kind of resigned to that and accepting of all of that. But of course, given his prodigious output over the years, he’d love it if people recognized more of the things that he does. But as I try to put across in the book, a lot of that has been the fault of record companies, marketing people who really couldn’t understand his music. The problem of a business is it’s very much kind of driven by fashion and it’s hard for a purer type of musician to get that kind of exposure and promotion. It has been hard for him from that point of view. But in the course of doing the book, I’ve played people things and they’ve been amazed—the power of his vocals, the complexities of some of his songs, [and] on the other hand some very simple, beautiful ballads. You could do a stunning Jack Bruce album just on the ballads he’s written. So there’s an awful lot there for people to mine.

What drives Jack Bruce?

What drives Jack Bruce?

If you asked Jack what he was, what he is, first and foremost he would say he’s a composer. He wouldn’t say he’s a singer or a bass player or a bandleader. He’d say he’s a composer, and from that point of view, you can be composing new songs, new albums, forever until you can’t do it anymore. And a good chunk of why I wrote this book, what I was trying to get across to people—in amongst all the stories about rock ‘n’ roll mayhem, which people like to read and that’s fair enough—is the fact that this guy had a forty-year music career. Cream was less than two years. And he has this hugely impressive catalogue of music that I really want people to just go out and listen to. Get a feel for some of the things that are mentioned, some of the musicians he worked with, some of the routes he took. Even reasonably well-versed Jack Bruce fans might not have picked on the albums that he did with Kip Hanrahan and all the Latin guys, which is completely different from the West, Bruce, and Laing and the BBM and the heavy rock kind of thing. He’s done opera, he’s done avant-garde jazz, he’s done big-band stuff. He’s just got this huge breadth, which means in some ways it’s been difficult for people who enjoy his music to keep up, really, because he just dives away into all these different highways and tangents. If something sounds interesting and different, he goes for it. As with all very intelligent, creative people, Jack gets bored very quickly with things and wants to move on to other things.

How have you grown as a songwriter? Can you discern any difference or progression?

How have you grown as a songwriter? Can you discern any difference or progression? Do you generally draw from your own experiences? Do you ever write from the standpoint of, say, a fiction writer creating altogether separate stories from what one sees or lives?

Do you generally draw from your own experiences? Do you ever write from the standpoint of, say, a fiction writer creating altogether separate stories from what one sees or lives?