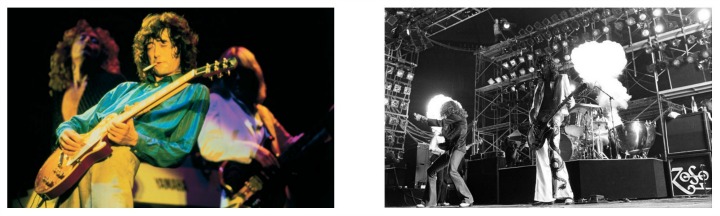

Barely in his twenties, yet with a half-decade of experience already under his belt, Preston was working at Atlantic Record's west coast publicity department in Los Angeles, tasked with photographing assorted gold-record presentations, press junkets, and parties whenever one of the label’s roster of artists rolled into town. It was at one such function that he met Led Zeppelin's imperious manager, Peter Grant, who in 1975 hired him as the band's official tour photographer, affording him exclusive and unfettered access to the band—Jimmy Page, Robert Plant, John Paul Jones, and John Bonham—and its coveted inner circle.

Onstage, backstage, aboard the band’s private jet—wherever Led Zeppelin rocked and roamed—Preston was there, observing his subjects with almost surreptitious intent, but picking his shots with discretion. He was on the payroll, after all. And so while he was essentially welcomed as one of their own, Preston heeded an unspoken pact not to photograph anything potentially incriminating or salacious.

When he wasn’t on the road with the band, Preston sought out new opportunities. He took portraits of the Jackson 5 and Iggy Pop, among others, and landed high-profile magazine covers like Rolling Stone and People—assignments which, particularly in the years after the band's demise (upon Bonham’s tragic death in 1980), have earned him near peerless distinction. An official photographer at Live Aid and six Olympic Games, he’s also immortalized moments on the concert stages of popular music's most influential and celebrated artists. Preston's live images of Bruce Springsteen in ‘85, Queen in ‘86, and Michael Jackson in ‘87, in particular, are definitive.

His experience with Led Zeppelin was seminal, though, and his images of the band continue to resonate with visceral, timeless intensity.

Led Zeppelin: Sound and Fury, a mammoth multimedia collection boasting over 250 photographs—including a hundred previously unpublished images—brings it all back in a vivid 300-page digital book, available exclusively on Apple's iTunes Bookstore. Along with select friends and insiders from that time, Preston offers insightful context throughout, whether in written narrative or in select audio and video commentary of what was, admittedly, the experience of a lifetime.

“You get a call to work for Led Zeppelin, yeah, it's a big deal,” Preston tells Write on Music. “This is the biggest band in the world. Sorry, Mick Jagger, but let's be honest here.”

In the book you write, “I never knew I was a good as I am.” Back when you were shooting Led Zeppelin was there any tipping point or revelatory moment where you thought, “Now I've got the hang of this. I'm not just snapping pictures here?”

It would've been way before I worked for Led Zeppelin. I'm a big fan of photography, period, and being a fan of photography I'm a big fan of photographers. I'm very fortunate in that I'm self-taught, completely self-taught. I never went to school for photography, never took any courses or anything. ... I chose not to go to college because I was already working in the business. I was already a working photographer.

When I picked up my first camera it just made sense to me. The analogy that I like to make is some 14-year-old kids get behind the wheel of a car for the first time—they may not know how to drive—but they instinctively know the relationship between the brake to the gas pedal to the clutch. You know what I mean? They get it. That's the way I was with my first camera. It's not even that it spoke to me; it was kind of in my DNA already, I guess. There's no other way to describe it.

It sounds like something a musician would say, actually. Like, the first time Eric Clapton picked up a guitar he didn't know the chords but he felt the instrument belonged in his hands.

Exactly. It feels right and you understand it. You may not know the technical end of it. Like you say, he may not have known how to play a #C or an #F or a #G chord, but he figured that out pretty quickly, and above and beyond as we all know. Same thing with a camera. I may not have understood how it worked, but I could very quickly figure out the relationship between the shutter speed and the f/stop, et cetera, et cetera, and it just made sense to me and I loved it from day one. ... What ended up happening was I realized that I had a talent for photographing people on stage. Obviously it's not all that I do or all that I've done in my career, but that came as naturally as the sun coming up in the morning. What's the point where I realized I had that talent? I don't know, but it was certainly before I worked with Led Zeppelin.

You also mention in the book about how you learned to recognize certain magical moments in the set, moments that would be repeated each night—like Jimmy Page leaping in the air during “Rock and Roll”—but you also write about having to be on guard for those magical moments that came up out of nowhere.

Yes, and that's all part and parcel of being a photojournalist. When I was growing up I used to read Life magazine and Look magazine. I loved those magazines. I've always been kind of a news junkie. I don’t know if you ever went to journalism school, but I’m sure you know enough that as a writer and as a journalist you observe and you are taught not to become part of the actual story. It’s the same with me. I’m there to observe. I know I'm doing my job when people don't even realize I'm around. I can't tell you how many times I've been working and someone from a band has come up to me and said, “You know, I didn't even realize you were here;” or, “I forgot you were here;” or, “You just blended into the scenery.” I don't take that as a derogatory remark; that’s a huge compliment. That tells me that I'm doing my job in a constructive way, in a professional way. And that's what a photojournalist does.

When you're working on a rock tour, you've got to be ready for... You're there to document what's going on. You're there to do a job whether it's for Led Zeppelin or Fleetwood Mac or Queen or Emerson, Lake, and Palmer—whomever. My job is to make sure I can deliver the photographs that my client needs for the purposes they need them for. To that end, I'm left to my own devices to get those photographs. There's a 24/7 component to all of this, if you will. It's always been easy for me to remain invisible or as much as possible, to be that fly on the wall.

From reading your narrative in the book and from my own knowledge and appreciation of Led Zeppelin’s career, the common thread that comes to mind is instinct. How you worked, how the band worked—even how Peter Grant managed the band and who he allowed in its inner circle—it all relied on instinct.

That's a really good thing you've picked up on, because Peter certainly worked by instincts and street smarts. I'm not a rock critic. I'm not a rock writer. I don't do that for a living, but what I know of them in terms of how they would work... It certainly was not a case of Jimmy or Robert or anyone saying, “Let's follow this road map,” or “Hey, we did a ballad. Now let's do a fast one.” It was certainly by instinct and what they wanted to do and how they felt. You would know better than I. You're a critic, and you would know more about those things. But there's certainly a modicum of trust involved. Peter took a liking to me and trusted me. He held the keys to the kingdom, let's be honest. If you couldn’t get past him—the lord high executioner or whatever you want to call him—that was it. So with Peter's blessing—and I do definitely mean with Peter’s blessing—I was hired. And I plowed ahead, and I was allowed to do what I do the way I do what I do.

Can you perceive in any constructive way how working with Led Zeppelin prepared you for the work you've done since?

That's a good question. Photographically I would say no. In terms of being a red-letter day, if you will, in the list of things I've done—a landmark job—certainly that helped a lot. As someone who has a career like I've had—and we both know there haven’t been that many people that have had this kind of a job, and there's less people that've done it well—it doesn't hurt when you can put that on your résumé, so to speak. What it might've prepared me for down the line was maybe just a reinforcement in my own mind that what I do and how I do it really does work for me and really can work for the biggest bands in this business, the most important bands in the business. ... It's a lot of pressure. It's a lot of work. You're working with four people with extremely strong personalities. You're working with a manager and a tour manager [Richard Cole], both of whom have extremely strong personalities. And it's a very cloistered bunch. Talk about being in the eye of the hurricane, man. That’s exactly what it felt like, but I never really had that kind of out-of-body experience, like, “Oh my God, I can't believe I'm doing this.” Or, if I had that thought it was fleeting at best because I was too busy doing my job.

You mentioned working with such strong personalities. That had to have helped you in later years, being able to deal with a diversity of personalities when you're photographing a Michael Jackson or a Freddie Mercury or a Bruce Springsteen—people who are known for being mercurial artists. That had to have been a pretty good foundation for dealing with those kinds of subjects.

Yeah, you're right. It wasn't a starting-off point because I'd already been working in the business, but yeah, you're right. Every tour, every shoot where you're working with someone like that, it helps the next one down the line. Absolutely. A lot of it goes back to another word you used, which was instinct. There's a lot of common sense involved. Look, I’m there to shoot the pictures that the band, the client, [or] the record company needs for whatever reason; that's what I'm hired to do. Over and above that, there are all those other elements involved that you have to be aware of that I believe are just a lot of common sense: Keep your fucking mouth shut. You don't need to tell Peter what Paul's saying, or vice versa. And you certainly don't need to act like you're the fifth member of the band. I'm lucky in that my ego doesn't require that. I don't need to walk on a tour plane with anybody with a big sign that says, “I am here, ladies and gentlemen.” Common sense tells you, shut your fucking mouth, keep your eyes open, keep your hand on the button, keep a roll of film loaded in the camera, and do your job.

Led Zeppelin: Sound and Fury by Neal Preston is available now exclusively at the iTunes Bookstore.

For more information on Neal Preston, please visit his official website.