On June 30, 1990 in Hertfordshire, England, on the stomping grounds of some of rock’s most historic, landmark events—the site of Led Zeppelin’s last stand on British soil, in ’79; where Freddie Mercury fronted Queen for the final time, in ’86—approximately 120,000 people descended upon Knebworth Park for a massive all-star concert benefiting the Nordof-Robbins Music Charity Centre and the Brit School for Performing Arts.

Long out of print in audio form (a DVD version was released in 2002), Live at Knebworth has at last been reissued, sounding just as dynamic as it did 20 years ago. Boasting a motherload of British music royalty, the double-disc set highlights extended performances by the likes of Paul McCartney, Elton John, Eric Clapton, Genesis, and Pink Floyd.

Given the random song selection, one could split hairs over which tracks made the cut—do you really need another live version of “Comfortably Numb”?—but on the whole it makes for a most enjoyable live album.

The “do-you-really-need-another” scrutiny could just as easily apply to the inclusion of other tracks like “Sunshine of Your Love” (Clapton), “Saturday Night’s Alright (For Fighting)” (Elton) or “Hey Jude” (McCartney). In the case of McCartney, though, it’s worth noting that he’d only begun playing a generous amount of Beatles songs in concert during the world tour he was on at this time, his first such road trip in 13 years. And on the heels of a momentous homecoming concert in Liverpool just two days before—where he poignantly paid tribute to John Lennon with a medley of “Strawberry Fields Forever," “Help,” and “Give Peace A Chance”—McCartney hit Knebworth in particularly high spirits, as his other featured track, a rambunctious take on “Coming Up,” revealed even further.

The “do-you-really-need-another” scrutiny could just as easily apply to the inclusion of other tracks like “Sunshine of Your Love” (Clapton), “Saturday Night’s Alright (For Fighting)” (Elton) or “Hey Jude” (McCartney). In the case of McCartney, though, it’s worth noting that he’d only begun playing a generous amount of Beatles songs in concert during the world tour he was on at this time, his first such road trip in 13 years. And on the heels of a momentous homecoming concert in Liverpool just two days before—where he poignantly paid tribute to John Lennon with a medley of “Strawberry Fields Forever," “Help,” and “Give Peace A Chance”—McCartney hit Knebworth in particularly high spirits, as his other featured track, a rambunctious take on “Coming Up,” revealed even further.

A more contemporary band didn’t stand much of a chance among all the legendary rockers on the bill, yet with “Badman’s Song,” Tears For Fears delivered one of the best (if not the best) performance of the entire show. In a fiery exchange, lead singer Roland Orzabal and the band’s best-kept secret, Oleta Adams — remember her anguished vocal on “Woman In Chains”? — summoned a menacing, 11-minute tour de force.

And so while one’s preferences will determine which selections they enjoy better than others, there really isn’t a bad track in the bunch. As an overview of Knebworth ‘90, it’s solid.

In a little bit over half an hour and through ten eclectic, well-crafted songs, Beth Thornley illustrates the possibilities and creative sweep of pop on her latest album, Wash U Clean.

Having written it, for the most part, on the piano, Thornley enriches the work with resonant, unmistakable melodies that wouldn't sound out of place on an early Elton John record. And in exploring a tapestry of styles both classic and contemporary, she holds it all together with the conviction she imparts in her voice.

Is there any one particular style that poses a great challenge for you as a songwriter? Do you take easier to writing a ballad, for instance, than to writing an upbeat song?

The different kinds of moods that are on the album, I feel pretty comfortable with. And even though it sounds like a large spread, because it all really falls under the melodic-pop umbrella, I’m okay with them. What I will never do is try to write a full-on R&B song. I’ll never try to write a full-on hip/hop song, or a full-on metal song. I mean, I borrow a little from R&B; I borrow a little from hip/hop. I don’t know that I borrow from metal; maybe I do a little bit. But whatever I’m doing is really going to fall under the melodic-pop umbrella. So I’m pretty comfortable as long as I don’t go too far in any of those directions. And what I really enjoy is writing with different feels. The fact that the grooves might change doesn’t bother me at all. I like that. And a lot of times I’ll have a groove in my head when I sit down to try to write a song so that I kind of know where I’m going. So if it made it to the album, it’s likely because I felt pretty comfortable getting it there.

Do you have to set time out to concentrate on songwriting or are you always quote, unquote, on?

Maybe a little of both. I do have a time of day I like to write and it’s in the morning. I like to get up and get a cup of coffee and sit down and spend at least two or three hours doing that. I can’t do it every day because sometimes I have other things I absolutely have to do. And on those days I’ll try at least in the afternoon to put an hour or something in. I’ve [also] got a little notebook, like so many other songwriters and musicians do. I have a notebook and a pen with me all the time. If I think of a lyric or an idea, I’ll stop and I’ll jot it down. So there are times when I actively am away from the house and I’m still thinking about music, and ideas might come to me and I’ll take the time to write them down.

You have an affinity for melody. Is that something that comes naturally for you?

You have an affinity for melody. Is that something that comes naturally for you?

No, I will try, three, four, five, ten melody ideas. If I get the chords that I like, I will spend a lot of time. I will usually write the first melody that comes to my mind. And then I’ll try to make it better. And then I’ll try to make it better again. And then I’ll try to make it better again until I feel I’ve done everything I can do with it. So it is not the first thing that comes out. Sometimes I go back to the first thing, but usually after I’ve tried several other approaches to make sure it’s what I want to do.

You strike an evocative, somber mood on the ballad, “What the Heart Wants.”

That was [about] a very painful experience. It finally got to be a relief by the time I got around to writing it; there’d been a long time between that break-up and when I finally wrote the song. The person I was breaking up with kept asking me, "Why are we breaking up?" but I just kept saying, "I don’t know. All I know is it’s what I need to do. I’m sorry." There was nothing wrong with this person; he was a fine person. It broke my heart. And I always knew it broke his more, but it broke mine too. For years I just never had an answer. He doesn’t even know I wrote the song. Or maybe he does. I’ve never called him to say, "Hey, I wrote a song about you." I don’t even know, if he knew that answer, if that would be a satisfying answer, but that was the only thing I could come around to. That was the best I could do.

You bookend the album with two infectious, upbeat songs ["Wash U Clean" and "A To Z"]. Was that intentional?

No, not intentional, except I did labor for quite a few days, no telling how many hours, over song order. There’s a lot of variety on the album, so just as soon as I would get into one mood there would be another mood. And I’d say to myself, "Does this mood follow that mood? Is it okay?" I tried so many different orders, and it just kept coming back to the one that ended up on the album. And “A To Z” just kept falling at the end and the more it showed up at the end, the more I thought, This is a perfect way to end the album.

It’s a great sign-off.

It’s a great sign-off.

I would never have thought about using it that way had I not had those particular songs to put in an order... I really felt like opening with “Wash U Clean” would be a good way to go. And ending with “A To Z” was kind of a good-feeling way to end. So I kind of stuck with those as my parameters and filled in the blanks.

You must be satisfied with how the album turned out.

I’m quite pleased and happy with it. I’m very happy. Maybe when I turn 80 and I look back and I see my albums laying side by side, I think I’ll still get a really happy feeling looking at this album. The colors on [the cover] are so pretty and some of the songs are just happy and fun. And I think that’s not a bad thing at all.

Wash U Clean is available now at outlets both retail and online. For more information on Beth Thornley, please visit the artist's official website.

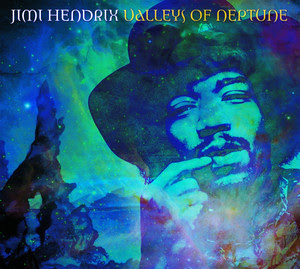

Jimi Hendrix released his third and what would turn out to be his final studio album, Electric Ladyland, nearly two full years before his untimely death on September 18, 1970. It’s worth noting, though, that his remaining time on the mortal plane wasn't downtime by any means.

While maintaining a fractured relationship with the Experience, he formed the Band of Gypsies with bassist Billy Cox and drummer Buddy Miles, toured the world over (issuing a live LP in the process), played at both Woodstock (’69) and the Isle of Wight (’70) and, perhaps most impressive of all, recorded a staggering accumulation of music.

Bits and chunks of that stockpile have surfaced over the years, circulating in assorted variations with inconsistent, often substandard quality. On the material culled for the recent release of Valleys of Neptune, however, the result suits the caliber of its creator. That’s not to say its production is flawless, though, as audio flubs sometimes crop up, but the performances in this case overwhelmingly transcend any incidental glitch or static buzz.

Still it’s hard to quibble over such technicalities once that familiar and blissfully distorted, erogenous guitar surges out of the past with the immediacy of here and now. Loaded with heavy riffs and rhythms, be it on the wanton, swaggering groove of “Ships Passing Through The Night” or in the urgent electric blues that barnstorm through “Hear My Train A Comin’” and a devastating cover of Elmore James’ “Bleeding Heart,” Hendrix coaxes these songs to his indulgent desire.

These are but a few examples, but they are indicative of the album as a whole. Valleys of Neptune is a potent concoction, and although it likely won’t redefine the context of his talent nor his creative potential had he lived longer, it presents Jimi Hendrix in a way that respects his artistic integrity and serves his legend remarkably well.

With songs both quirky and endearingly candid, singer/songwriter Amber Rubarth is a refreshing talent on the rise. As illustrated on her third and latest LP, Good Mystery, she complements a gentle, folk/pop vibe with a storyteller’s engagement and the unassuming, often-awkward charm of a girl you wished lived next door.

While gearing up for next week’s SXSW Music Festival, where on March 18 she’ll deliver an official showcase performance, Amber Rubarth spoke with Donald Gibson about Good Mystery and her craft overall.

How do you take to songwriting? Is it challenging for you? Is there a discipline you have to apply?

Most of the songs that are keepers and that I usually like the most tend to be the ones that I write pretty quickly, maybe over two or three days, kind of obsessively. And it’s mostly because I have something that I need to figure out and that’s the only way I know of doing it. [Laughs] But one thing I’ve learned recently from writing with other people is that sometimes it’s good to work a lot on a song and do it out of discipline, to prompt yourself to write a song rather than just waiting for it to come to you. So there are a few I’ve written more like that.

On Good Mystery, a song you play on piano, “The Stairway,” is striking. Are you trained on the piano?

I’m not trained [but] I’ve played since I was a kid. My brother was taking lessons — he’s a year and a half older than me — and I don’t remember this, but my mom said she just came home one day when I was three and I was playing all the things that he had learned in his lesson. So I played a tiny bit when I was really young like that. And then I didn’t have a piano for a long part of growing up and I started up again in high school, playing on a little keyboard that I had. But I don’t know any of the theory or anything like that. A lot of times — I don’t remember if “The Stairwell” was like this — I’ll wake up and have an entire thing in my head that’s all [on] piano. And I had this as a kid also where I’d have an entire song in my head and I remember being really angry because I couldn’t actually play it. So now I’m trying to learn more piano and study it a little bit better or at least practice it a little more.

“Wish We’d Gotten Drunk” is an adorable song, by the way.

I wrote that in about fifteen minutes and I really didn’t think I was going to play it for anybody. I was so embarrassed that I’d written it that I thought, I just wrote this for myself and nobody in the world will ever hear this. [Laughs]

You’ve been quoted as saying that, growing up, you were very shy. How do you reconcile that as a live performer?

For some reason, I feel shy when I’m about to go on stage; I feel shy after the show is over. But somehow, when I’m on stage, “shy” doesn’t even feel like something that would enter my head. Not that I feel not shy, but it feels like that emotion doesn’t belong with playing music.

Having written songs for a few years now, can you discern a difference now from how you wrote three or four years ago?

When I first started writing, my thing was writing about wanting to do what I really loved doing, almost motivational songs, which helped me in some ways to actually do it. I think my style now is not always [as] straightforward. That’s one thing I’ve started playing with a bit that I never did before. Before it was about trying to find something really, really honest that I could say in a song that I might not be able to say in person to somebody, whether from shyness or just being scared. But now I really like — I think maybe this is something I probably got from listening to Randy Newman, which is a new thing for me; or also reading Mark Twain — the idea of an unreliable narrator.

You mentioned that — more so when you were younger — you wrote songs to get certain things out of your system or to say things you felt needed saying. What keeps you going as a songwriter now?

That might go back to the shy thing. Also, I need some outlet. I have friends, but I don’t always talk to people about everything. So I think that it’s sort of my outlet. In the last two years, I’ve done even more of talking to people through a song, which I don’t know if it’s healthy or not. [Laughs]

It’s probably healthy for you, maybe not for them.

Who knows? [Laughs] A lot of times when I’m thinking about something, I hear music with it. Even if it’s something where I’m trying to figure something out, like I’ll come up with a line and have a melody to the line. Or I’ll just come up with music to fit the mood that I’m feeling. I guess that’s just happening in my head anyways.

For more information on Amber Rubarth, please visit the artist’s official website.

In the case of Clarence Greenwood, better known as Citizen Cope, the songwriting process owes as much to intuitiveness as it does to technique or ability. In the eight years since the Brooklyn-based (by way of Washington DC) artist’s critically acclaimed, self-titled debut, he’s turned out a handful of inspired albums, with each one intended at enriching “an overall artistic statement,” he says. “And each new record will give new life to the other music. I think that’s the best you can do when you make music.”

Citizen Cope furthers that philosophy on his latest work, The Rainwater LP, issued digitally last month and in physical distribution this week. Amid a hodgepodge of sonic styles he’s become known for drawing upon — everything from folk and blues to hip/hop and soul — he brings altogether fresh, to-the-bone commentary and perspective to his lyrics this time around. And underscoring the cumulative context in which he perceives his craft, he says of “Lifeline,” one of the album’s strongest tracks, “There’s something about that song that I don’t think I could’ve written before. I had to have written all those other songs to get to that song.”

Currently on an extensive tour in support of The Rainwater LP, Citizen Cope checked in with Donald Gibson to shed a bit of light on how inspiration informs his music.

How do you measure your progress as a songwriter to ensure you’re not just recycling the same things?

You just got to follow your muse, what inspires you. People will say, “Why don’t you write the kind of songs that were on the first record?” with all the characters and this kind of stuff. And Clarence Greenwood was a personal journey of trying to persevere through something difficult, having there be something great on the other end. Then Every Waking Moment was more of a love record, but [it] also questioned political times. This record [The Rainwater LP] is just a real personal record.

When you write, there’s these different emotions that come up at different times in your life where you might be pissed off about something and write a song like “Comin’ Back” and then you might be desperate and write a song like “Salvation” [both tracks from Citizen Cope]. All the different songs have their own emotions and people identify with [those]. I think those are just as powerful as the meaning behind the record.

You don’t tour with the people you record with. Do the session musicians foster your creativity or do you come to the studio with fixed ideas of how you want it to go?

Pretty fixed ideas. I really look, when somebody’s going to play on a record, at their tone and their feel; also, their ability to make something better than it could’ve been... There’s something about the way Preston [Krump, on bass] plays something that makes it sound better. There’s something about the way James Poyser plays the piano that makes it sound better; his touch, his feel is remarkable. Bashiri Johnson [on percussion] gets on a record and it sounds like a record. As a producer, you try to put the elements around you that work.

Does living in Brooklyn and the New York City area have an effect on your music that, say, if you lived in Los Angeles you wouldn’t get?

I think it’s a culmination of your life, the music that you do. And it just kind of evolves and your sound evolves and goes in a new direction. I always thought about that, If I hadn’t of left DC, would I still have written these songs? It’s kind of where you’re centered at… Whatever inspires you is probably pretty deep within and not as much as a surface of time and place.

For more information on Citizen Cope, including tour dates and locations, please visit the artist’s official website.

The “do-you-really-need-another” scrutiny could just as easily apply to the inclusion of other tracks like “Sunshine of Your Love” (Clapton), “Saturday Night’s Alright (For Fighting)” (Elton) or “Hey Jude” (McCartney). In the case of McCartney, though, it’s worth noting that he’d only begun playing a generous amount of Beatles songs in concert during the world tour he was on at this time, his first such road trip in 13 years. And on the heels of a momentous homecoming concert in Liverpool just two days before—where he poignantly paid tribute to John Lennon with a medley of “Strawberry Fields Forever," “Help,” and “Give Peace A Chance”—McCartney hit Knebworth in particularly high spirits, as his other featured track, a rambunctious take on “Coming Up,” revealed even further.

The “do-you-really-need-another” scrutiny could just as easily apply to the inclusion of other tracks like “Sunshine of Your Love” (Clapton), “Saturday Night’s Alright (For Fighting)” (Elton) or “Hey Jude” (McCartney). In the case of McCartney, though, it’s worth noting that he’d only begun playing a generous amount of Beatles songs in concert during the world tour he was on at this time, his first such road trip in 13 years. And on the heels of a momentous homecoming concert in Liverpool just two days before—where he poignantly paid tribute to John Lennon with a medley of “Strawberry Fields Forever," “Help,” and “Give Peace A Chance”—McCartney hit Knebworth in particularly high spirits, as his other featured track, a rambunctious take on “Coming Up,” revealed even further. The “do-you-really-need-another” scrutiny could just as easily apply to the inclusion of other tracks like “Sunshine of Your Love” (Clapton), “Saturday Night’s Alright (For Fighting)” (Elton) or “Hey Jude” (McCartney). In the case of McCartney, though, it’s worth noting that he’d only begun playing a generous amount of Beatles songs in concert during the world tour he was on at this time, his first such road trip in 13 years. And on the heels of a momentous homecoming concert in Liverpool just two days before—where he poignantly paid tribute to John Lennon with a medley of “Strawberry Fields Forever," “Help,” and “Give Peace A Chance”—McCartney hit Knebworth in particularly high spirits, as his other featured track, a rambunctious take on “Coming Up,” revealed even further.

The “do-you-really-need-another” scrutiny could just as easily apply to the inclusion of other tracks like “Sunshine of Your Love” (Clapton), “Saturday Night’s Alright (For Fighting)” (Elton) or “Hey Jude” (McCartney). In the case of McCartney, though, it’s worth noting that he’d only begun playing a generous amount of Beatles songs in concert during the world tour he was on at this time, his first such road trip in 13 years. And on the heels of a momentous homecoming concert in Liverpool just two days before—where he poignantly paid tribute to John Lennon with a medley of “Strawberry Fields Forever," “Help,” and “Give Peace A Chance”—McCartney hit Knebworth in particularly high spirits, as his other featured track, a rambunctious take on “Coming Up,” revealed even further.