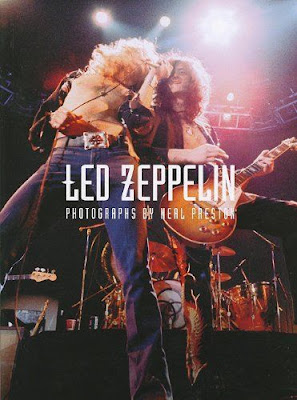

“We’re not talking about The Vagrants from Long Island or Vanilla Fudge, or the horn section of Tower of Power. This is Led fucking Zeppelin.”

Such is how Neal Preston recalls his enviable and utterly daunting role as the official photographer for the heaviest band on the planet. In Led Zeppelin: Photographs By Neal Preston, the man behind the lens has compiled some of his most resonant shots of Robert Plant, Jimmy Page, John Paul Jones, and John Bonham, rendering moments both epic and strikingly poignant.

Interspersed throughout the photos is an interview conducted by KLOS-FM Los Angeles radio host Cynthia Fox, in which Preston reflects upon his experiences, adding context to certain images while explaining the scope of his responsibilities at the time. In short, he didn’t merely snap pictures for a couple of hours at whatever venue Zeppelin had landed in on any given night.In looking at the live shots, in particular—be it one of Page shredding a double-neck or of all four musicians working in synergy—you can feel the music. In other words, Preston captures a spirit as well as his subjects, compelling you to envision bearing witness to “Achilles Last Stand” at Chicago Stadium in ’77 or “Since I’ve Been Loving You” at Madison Square Garden in ’70.

Complementing the concert photographs are select portraits and behind-the-scenes snapshots that reveal a bit of innocence behind the band’s menacing enigma. It’s especially evident in shots like that of Bonham napping on board the Starship (Zep’s private jet) or of Plant walking arm in arm with his young daughter, Carmen, backstage at Knebworth.

Any depictions of the band’s notorious debauchery are kept to a minimum—a candid shot of Jimmy Page swigging from a bottle of Jack is about as salacious as it gets here—but it should be emphasized that Preston was employed by and under close scrutiny of the band and Peter Grant, Zeppelin’s imperious manager. Ultimately, any potentially compromising or unflattering shots (especially with promiscuous girls or illicit substances and paraphernalia) would’ve likely been canned back when they were developed—if not sooner.

Any depictions of the band’s notorious debauchery are kept to a minimum—a candid shot of Jimmy Page swigging from a bottle of Jack is about as salacious as it gets here—but it should be emphasized that Preston was employed by and under close scrutiny of the band and Peter Grant, Zeppelin’s imperious manager. Ultimately, any potentially compromising or unflattering shots (especially with promiscuous girls or illicit substances and paraphernalia) would’ve likely been canned back when they were developed—if not sooner.

What Neal Preston so strikingly achieves with this collection is to reflect Led Zeppelin in ways that live up to—and in many cases, enrich—the band’s larger-than-life reputation while not compromising the integrity of his own work as a professional photographer.

Perhaps it would be easy to suggest she sounds good for her age, but 19-year-old singer/songwriter Lindsey Mae possesses the sort of talent that’s remarkable by any standard. On her self-titled, debut EP, she draws upon folk and pop in songs as engaging as they are well-written, singing them in a voice that is at turns winsome and impressionably coy.

She wraps acoustic-laden arrangements around picturesque metaphors and imagery, imparting the nervous rush of infatuation with moments of self-consciousness and awkward uncertainty that inevitably come along with it. Throughout the EP’s five tracks—which were produced by Hal Cragin (A Fine Frenzy)—Lindsey Mae demonstrates genuine empathy and sophistication, two qualities which will serve her well as she continues to develop her creativity.

As unaffected and sincere in her demeanor as she is in her music, Lindsey Mae graciously took some time to speak about her craft and ambition.

On the biography you wrote on your Myspace page, you say that you find writing fascinating. A lot of songwriters actually dread it. They like having written a song, but they don’t particularly enjoy the process. What about songwriting fascinates you?

For me, I’ve always been the kind of person to use writing as a way to speak. Most people who meet me say that I’m a very shy and reserved person. So my way of expressing how I feel is through writing. And it’s always fascinating to me because it’s amazing what comes out [on] paper that sometimes you just can’t say to people. And music’s my way of sneaking out things that I really want to say but I really can’t say. I turn all my poetry and all my writing into my songs.

What do you find as the most challenging aspect of songwriting?

I definitely find coming up with new chord progressions [on the guitar] the hardest part. My dad played bass guitar, so he taught me a few basics, but other than that I was pretty much on my own. I’ve kind of been coaching myself.

You have a real affinity for melody.

You have a real affinity for melody.

I love it. Love it.

Do the melodies just come to you or does it take a great deal of effort to work them out?

Usually, they just come to me. For example, there was a day last week [when] I was just getting on the subway and I just started humming this melody. And I just pulled out my phone and recorded it. I came back and wrote a song.

That’s a pretty good day.

It was a good day! [Laughs]

How are you enjoying playing live?

Oh, I love it. That’s the best part of it. When some of my friends come out—and they’re so cute—they’ll sit up really close and they’ll sing all the songs. It’s an awesome feeling, especially meeting people. One person had traveled over an hour to get to a show I played in Philadelphia once. And she absolutely loved it. She was like, “I’m one of your biggest fans!” It just made my day. It’s the best feeling ever.

No stage fright?

I’ve always had stage fright, ironically, but I kind of get the feeling, like, I’m in my bedroom just practicing, but for a bunch of people. I always get that little butterfly, tingly feeling, but for me, that’s the reason why I do it—because it feels good.

In working with Hal Cragin, what has he brought to your music? How has he helped shape it?

Once people get to know me, I’m not that shy and reserved. He brings out the liveliness of my personality in the music... [He] literally puts who I am in music form. And I love it.

How do you see yourself as an artist evolving in the future?

I’m just going to do it one fan at a time... We’ve gone on three different tours this past year. This [coming] year, I’m going to try to do that again. We just played smaller venues all around the Northeast. One by one, we started building a little fanbase. To me, that’s fun.

My favorite song on the EP is “Paper Mache.” Is there a story behind that?

A lot of those songs—“Paper Mache,” “Time,” and “The Way You”—were all about dreams that I’ve had. A lot of the songs that I write are just about daydreams where I imagine this little romantic situation or what I feel about love or whatever. There’s always a certain situation with a guy without a face. So I’m just writing about hope for love that I’m dreaming of.

Check out Lindsey Mae's Myspace page for more information on her music and live dates. She is currently at work on her first full-length album, which is due out next year.

Released this week on DVD, Leonard Cohen: Live At The Isle of Wight 1970 chronicles the singer/songwriter’s landmark set at the five-day music festival in England. Directed by Academy Award winning filmmaker Murray Lerner—whose credits include Message To Love: The Isle of Wight Festival 1970, The Other Side of The Mirror: Bob Dylan At Newport and Amazing Journey: The Story of The Who—the documentary renders Cohen as the infamous event’s saving grace.

Despite an unprecedented audience of 600,000 and a roster of high-profile acts from The Who and Joni Mitchell to Sly & The Family Stone and Jimi Hendrix, the massive happening quickly took on an iniquitous subtext. Tension between many in the crowd and the concert organizers (who hadn’t prepared for such staggering attendance) was inevitably directed toward the artists, resulting in a climate of random disruptions and resentment.

It’s within this context that Lerner frames Cohen’s performance, interspersing it with present commentary by other artists, including Joan Baez and Kris Kristofferson, who were also on the bill.

Murray Lerner recently spoke to Donald Gibson about his latest film as well as his thoughts on Dylan and the essential power of music.

There are a lot of sustained close-ups on Cohen’s face, which seem to reflect the way the audience was paying attention to him.

Excellent point. I think he made them feel very intimate with him. And I wanted to show that. He was the only one that I can think of, out of all the performers, who actually expressed sympathy and consensus with the audience’s ideals and feelings. [When] he in a sense said, “We’re a nation, but we’re weak. We need to get stronger,” he was telling the audience that he was on their side ideologically.

He was empathetic.

He was empathetic.

Yeah. Therefore, I think that meant a lot. A lot of the performers were upset with the audience—and rightly so because of the conditions… As Joni [Mitchell] was saying, “Please give me some [respect].” In other words, be aware of my feelings. She wasn’t saying, “I’m aware of your feelings.”

She was basically saying, “I need you to quiet down so I can do my thing.”

Right—“I’m an artist and this is my life.” She wasn’t saying, “Well, you’re in a bad position; I understand why you’re doing this.” But [Cohen] was. He wasn’t being clever; I think that’s just what he really felt… He was one with the audience almost instantly… Ordinarily a quiet, acoustic set wasn’t their thing… The thing is, though, he was there for them. [Also], T.S. Eliot said, “[Genuine] poetry can communicate before it is understood.” And as Joan Baez said [in the commentary], she didn’t understand a lot of it, but it worked. That’s true. Because of that, they were really listening.

Also in the commentary, Kris Kristofferson suggests that one of the reasons the crowd didn’t turn on Cohen was because he wasn’t intimidated by them.

Right. He was very prepossessing. He was his own man and he wasn’t really feeling adversarial.

Having filmed Dylan at Newport, particularly in ’65, and then Cohen five years later at the Isle of Wight, how would you contrast their relationship to the audience?

That’s a good question. It was a big contrast. The audience booed in ’65—not the whole audience, [but] in a way, it was the opposite of Cohen. To me, the music was absolutely hypnotic and mesmerizing with Dylan; I loved it. Now, people were thrown by the unexpectedness of it, but if you think about it, the lyrics reflected what the audience felt. He was talking about their feelings, the alienation of young people. It’s a very mysterious thing because I guess they didn’t respond to the lyrics. They responded to…

The volume.

The volume, right, the electric part of it, which I thought was great. I don’t think it’s volume [though] that creates the power of electric music. It induces a kind of hypnosis in the body, gets into the nerves. It’s always fascinated me.

What is it about music in general or music performance specifically that has interested you as a primary subject to document?

I was fascinated with how a performer used the power of music to relate to the audience. I think that’s really my constant theme. But someday I want to make a film about the power of music. It’s an amazing phenomenon… What does it mean to get 100,000 people—or 600,000 people—in concert? They want something that the music gives them but also that the music allows [for] them to be together with other people.

It’s communal.

It’s a communal activity. People evidently need that. Why, we don’t know, but they do.

At 22, Robert Francis evokes the wayward spirit of a much older soul.

The impression is one Francis first made with his strikingly mature 2007 debut album, One By One (Aeronaut Records), on which his skills as a singer, songwriter, and guitarist crystallized in songs and themes that belied his youth. In addition to the critical praise that came his way, his pensive narratives and overall craftsmanship earned Francis comparisons to hardcore troubadours Townes Van Zandt and Steve Earle.

Having signed with Atlantic Records, Francis ups the ante with his current sophomore effort, Before Nightfall. Available now on iTunes and everywhere else on Tuesday (October 20), the album courses with a feral intensity through moments both sobering and soulfully uplifting.

Also on Tuesday, Francis will embark on a national tour—supporting indie band Noah and the Whale—at the Roxy in Hollywood. In preparation for the release of Before Nightfall, Robert Francis spoke about the making of the album as well as his expectations for himself down the road.

Now that you’re on a major label, was there any major difference in how you approached this album in comparison to your first one?

There were subtle differences. For a while, I was making my best effort to produce the record myself, which the label supported, but was also a little bit hesitant to follow through with given my reputation for starting projects and never finishing them. We started it off by [going] to Palm Springs. The label gave us money. We had to go out there and set up a studio in the desert, tried to record there. And I was feeling like the songs were never coming across the way I felt they should have. But then I got a call from Dave Sardy [producer, Before Nightfall] and I met him in London about two years ago when he was working on the Oasis record [Don’t Believe the Truth]. I don’t think he’s known for being the easiest person to work with or the nicest guy, but I think he’s great. He’s really serious; and I am too. [For] the vocal approach, he got a little more out of me than I had ever expected. As far as the record, it’s just the band playing; it’s pretty stripped down. Minimal overdubs, cut pretty quickly, and in about three weeks it was finished.

How have you grown creatively since One By One?

With One By One, I had all the time in the world to go down every avenue, to see what worked and what didn’t. That’s why that record took me about a year to make. I tried doing different things. With this record, with my songwriting, I knew exactly what I should be doing. This record was really about capturing the place I was right at those moments—not so much looking back in time or capturing nostalgia. That was the way I felt at those exact moments when we got it on tape.

Did it end up how you hoped it would?

Nothing ever ends up the way I hope it will… I’d sort of gotten used to singing with subtle affectations in my voice, used to layering, like, strings and reverbs. What I kind of came to terms with was that I was hiding. Hiding behind a lot of different idiosyncrasies and nuances. What happened here [was] at first I was worried, [but] then the more I listened to it, I became a bit more confident. Now I think it’s the best thing I could’ve done.

When you say you were hiding, are you saying it as far as imparting emotions or as far as a vocalist?

Everything. Lyrically. Emotionally. On this record the vocals are so up front; they’re very personal. It’s easy to take away from the message by adding other things, other instruments, focusing on that more than what is really at the core.

When you say you were hiding, are you saying it as far as imparting emotions or as far as a vocalist?

Everything. Lyrically. Emotionally. On this record the vocals are so up front; they’re very personal. It’s easy to take away from the message by adding other things, other instruments, focusing on that more than what is really at the core.

How do you see yourself evolving as an artist over the years?

My main goal would be to look back, when I’m 35 or 40, and have an album set out for me for every year of my life that I can look back on. Where I can listen to this record or this song and pinpoint the way I felt at that moment in time. That’s my goal. And also to never really repeat myself.

You’ve already been compared to Townes Van Zandt, Jeff Buckley, Steve Earle. Do these comparisons inspire you or intimidate you? How do you even process something like that at this stage?

To be honest, I never really think about it. I remember when One By One came out, that’s when most of the Townes Van Zandt, Steve Earle comparisons came. And I can understand. It was exciting to hear when I’d just turned 19...

And you get compared to these bad-ass icons.

Yeah, that wasn’t so bad. After a while [though], there’s only so much you can do. I was writing in a similar vein, then. It’s more difficult for me to put a finger on who’s influencing me [now] because it’s sort of becoming a more natural sound. I can’t tell where the influences are coming from; I think everything is just coming in line.

For more information on Robert Francis as well as his upcoming tour with Noah and the Whale, visit his official website or Myspace page.

Considering the eclectic dimensions of her music, it’s become increasingly hard to put a line on Erin McKeown. On her official website, though, she calls herself a “funky folk artist” and — so long as if by “funky” she means more “free-spirited and quirky” and less “she’s a very kinky girl, the kind you don’t home to mother” — the description seems just about right.

At least that's how she's come across in the past on great records like Grand and We Will Become Like Birds. And that's likely how she intended to come across on her latest release (out Tuesday, October 13) on the Righteous Babe label, Hundreds of Lions.

Essentially a hit-and-miss effort, however, the album lacks the overall quality and cohesion she’s proven herself capable of producing time and again. There are redeeming moments to be sure, which besides their inherent quality further underscore how much better the rest of this work could have been. The witty and wonderful opening track, "To A Hammer," is one such (albeit fleeting) indication.

The standout here is "The Lion," which best reflects McKeown's creative depth and quirky imagination. She tells a blissfully tongue-in-cheek, metaphorical tale of circus lovers (both of them acrobats!) that serves as a commentary on negative perceptions toward homosexuality (which she coyly refers to as "the freak show our mothers warned us about"). The music is as precocious as the narrative, its sing-a-long chorus yielding to more eccentric fits and starts of musical theater.

Other highlights include "28" — which is immersed in a pensive, spectral aura even as it succumbs to a glorious onslaught of percussion — and, while originally introduced on McKeown’s live album, Lafayette, “You, Sailor” maintains the austerity of that solo performance to yield one of this album’s most tender moments.

The tracks that round out Hundreds of Lions, in one way or another, are bereft of the distinctions that the ones mentioned have in spades. From the indiscriminate haze of "The Boat" to the electronica lament of “All That Time You Missed” to the morbid and monotonous dirge of “(Put The Fun Back In The) Funeral” — its refrain of “I can’t breathe” echoed ad nauseum — most of them seem to suffer from a lackadaisical malaise.

Anyone familiar with Erin McKeown's music knows that lethargy isn't her strong suit. She's a strikingly resonant songwriter and a vibrant performer. A good portion of songs on this album is a testament to that; unfortunately, a greater portion is not.

The standout here is "The Lion," which best reflects McKeown's creative depth and quirky imagination. She tells a blissfully tongue-in-cheek, metaphorical tale of circus lovers (both of them acrobats!) that serves as a commentary on negative perceptions toward homosexuality (which she coyly refers to as "the freak show our mothers warned us about"). The music is as precocious as the narrative, its sing-a-long chorus yielding to more eccentric fits and starts of musical theater.

Other highlights include "28" — which is immersed in a pensive, spectral aura even as it succumbs to a glorious onslaught of percussion — and, while originally introduced on McKeown’s live album, Lafayette, “You, Sailor” maintains the austerity of that solo performance to yield one of this album’s most tender moments.

The tracks that round out Hundreds of Lions, in one way or another, are bereft of the distinctions that the ones mentioned have in spades. From the indiscriminate haze of "The Boat" to the electronica lament of “All That Time You Missed” to the morbid and monotonous dirge of “(Put The Fun Back In The) Funeral” — its refrain of “I can’t breathe” echoed ad nauseum — most of them seem to suffer from a lackadaisical malaise.

Anyone familiar with Erin McKeown's music knows that lethargy isn't her strong suit. She's a strikingly resonant songwriter and a vibrant performer. A good portion of songs on this album is a testament to that; unfortunately, a greater portion is not.

A recurrent subtext of voyeurism runs through Trust: Photographs of Jim Marshall. The connotation isn’t seedy or even surreptitious, mind you, but rather it surfaces in how its subjects often seem oblivious to being so intently observed, let alone professionally photographed.

Edited by Dave Brolan, Trust renders an evocative and, at times, poignant look through the lens of renowned photographer Jim Marshall, who in his extensive (and still ongoing) career has documented some of music’s most iconic events (Monterey, Woodstock, Altamont) as well as its most influential artists.

Marshall's own annotations accompany each photo, lending insight and endearing reminiscences. And while assorted portraits fill out the pages—The Who in ’68, up against a wall at their San Francisco motel; Hendrix in '67, perched at a drum kit during soundcheck at Monterey; Jagger in ’72, arms crossed and pouting in boyish defiance—the shots that capture artists in action or otherwise unaware are the ones that resonate most.

Like a print journalist covering his beat, Marshall long ago took to embedding himself in the environment of his subjects so as to become inconspicuous among them. In so doing, he established a rapport that afforded him the opportunity to shoot when or wherever he wanted without pretense or undue distraction.

Like a print journalist covering his beat, Marshall long ago took to embedding himself in the environment of his subjects so as to become inconspicuous among them. In so doing, he established a rapport that afforded him the opportunity to shoot when or wherever he wanted without pretense or undue distraction.

Such is how he caught artists at their most candid and in their own element, like Miles Davis looking especially pensive at the Isle of Wight, Mahalia Jackson gloriously wailing away at Carnegie Hall, and the Beatles chatting with journalist Ralph Gleason before taking the stage at San Francisco’s Candlestick Park for what would turn out to be the band’s live farewell. “[T]o this day I don’t believe they knew it would be their last concert,” Marshall asserts.

In Trust: Photographs of Jim Marshall are images of mortals living up to—or contending with—their own epic reputations, their own demons, and their own brilliant myths. It’s a fantastic collection from front to back.

For any actor or actress, taking on a role that suits one’s strengths can make or break even the most well-intentioned performance. It’s much the same in music and, in the case of Scarlett Johansson—who last year debuted with an album of Tom Waits covers (save for one original)—her approach didn’t suit the script, so to speak. The result, Anywhere I Lay My Head, was a techno-laden disappointment underscored by vocals that sounded awkward and bizarrely removed.

Enter Pete Yorn, who on Break Up has written eight original duets (save for one cover)—conceived in the spirit of Serge Gainsbourg’s 1960s star-crossed recordings with Brigitte Bardot—creating an ideal vehicle for Johansson to blossom as a vocalist. Amid a swirl of ambrosial melodies and playful (often cartoonish) effects, she sounds refreshingly natural and fetching.

It’s the chemistry between the two, however, that ultimately redeems the songs. Yorn and Johansson hem and haw through the fuzz-toned flurry of “Relator,” laying their relationship on the line at the outset—“You can leave whenever you want out,” they sing—setting the tone for its imminent demise. They strike similar resonance with the ominously titled “Blackie’s Dead,” their back-and-forth vocals benefiting from a swift, catchy beat.

Like any other love on the rocks, though, the couple that comprises this one is riddled with insecurity and should-I-stay-or-should-I-go doubt. “I’m so confused by you,” each concedes in “I Don’t Know What To Do,” before reminiscing through rose-colored glasses, “But when you’re with me, darling/I don’t believe in anyone else.” Inevitably, such warm-and-fuzzy feelings don’t linger too long (three minutes, thirty-one seconds to be exact); otherwise the album would’ve been called Make Up.

Like any other love on the rocks, though, the couple that comprises this one is riddled with insecurity and should-I-stay-or-should-I-go doubt. “I’m so confused by you,” each concedes in “I Don’t Know What To Do,” before reminiscing through rose-colored glasses, “But when you’re with me, darling/I don’t believe in anyone else.” Inevitably, such warm-and-fuzzy feelings don’t linger too long (three minutes, thirty-one seconds to be exact); otherwise the album would’ve been called Make Up.

And so as they drift further away from each other, the music in turn grows more spatial and aloof, but never dull. Even in the woozy haze that looms through cuts like “Clean” and an abstract cover of Chris Bell’s “I Am The Cosmos,” Yorn and Johansson still summon an occasional glimmer of levity.

Break Up is a charming album all around, one which not only demonstrates the evolution of Pete Yorn’s talent but, for Scarlett Johansson in the realm of music, the promise of hers as well.

Any depictions of the band’s notorious debauchery are kept to a minimum—a candid shot of Jimmy Page swigging from a bottle of Jack is about as salacious as it gets here—but it should be emphasized that Preston was employed by and under close scrutiny of the band and Peter Grant, Zeppelin’s imperious manager. Ultimately, any potentially compromising or unflattering shots (especially with promiscuous girls or illicit substances and paraphernalia) would’ve likely been canned back when they were developed—if not sooner.

Any depictions of the band’s notorious debauchery are kept to a minimum—a candid shot of Jimmy Page swigging from a bottle of Jack is about as salacious as it gets here—but it should be emphasized that Preston was employed by and under close scrutiny of the band and Peter Grant, Zeppelin’s imperious manager. Ultimately, any potentially compromising or unflattering shots (especially with promiscuous girls or illicit substances and paraphernalia) would’ve likely been canned back when they were developed—if not sooner. Any depictions of the band’s notorious debauchery are kept to a minimum—a candid shot of Jimmy Page swigging from a bottle of Jack is about as salacious as it gets here—but it should be emphasized that Preston was employed by and under close scrutiny of the band and Peter Grant, Zeppelin’s imperious manager. Ultimately, any potentially compromising or unflattering shots (especially with promiscuous girls or illicit substances and paraphernalia) would’ve likely been canned back when they were developed—if not sooner.

Any depictions of the band’s notorious debauchery are kept to a minimum—a candid shot of Jimmy Page swigging from a bottle of Jack is about as salacious as it gets here—but it should be emphasized that Preston was employed by and under close scrutiny of the band and Peter Grant, Zeppelin’s imperious manager. Ultimately, any potentially compromising or unflattering shots (especially with promiscuous girls or illicit substances and paraphernalia) would’ve likely been canned back when they were developed—if not sooner.