Imagine yourself facing the task of telling Tony Bennett during a recording session that he’s hit a few bum notes. Not only should you have the credible acumen for identifying such flaws, but also the knowledge of how to correct them. Fortunately, Phil Ramone has an abundance of both. One of music’s most prolific and distinguished producers, he candidly shares experiences from his career in his new book, Making Records: The Scenes Behind The Music.

While neither a strict memoir nor a technical manual, the book blends elements of the two, usually within the context of representative and applicable anecdotes.

Ramone writes an engaging account of his ascension in the music industry, from working as a studio apprentice to engineering recording sessions and ultimately producing albums and live events. As a result, the reader gains priceless insight on some landmark recordings as well as perspective on the evolution of music production over the last 50 years.

What makes this book such an enjoyable read is the producer’s unassuming way of relating his memories and knowledge. One would suspect that someone as proficient and experienced as Phil Ramone would have, by now, lost all sense of wonder in regard to how music is made. Quite the contrary, while he undoubtedly knows what he’s doing in the studio, he seems just as amazed and inspired by the creative process as any typical fan would feel.

Fans of Billy Joel, in particular, will take pleasure in reading what Ramone recollects about producing many of the Piano Man’s greatest albums. He recounts how certain iconic sound effects were achieved, like the shattering glass that opens “You May Be Right” and the reverberating helicopter propellers that bookend “Goodnight Saigon.” He explains his view on what was lacking in Joel’s first four albums—which he didn’t produce—and why that deficiency resulted in releasing Songs From The Attic. He even divulges how he would humorously blackmail Joel and his band into working whenever they got hungry or distracted.

In sharing his experiences of working with Billy Joel, Barbra Streisand, Frank Sinatra, Ray Charles, and a plethora of others, the consistent factor is how Ramone approached (and still approaches) each project with the artist’s intent foremost in his mind. He astutely notes that his name doesn’t appear on the covers of the albums he produces. Thus, instead of attempting to conform an artist to a certain style or standard, he respects and caters to each artist’s creative goal.

At the same time, Ramone justifiably points out the credentials that he brings to the making of an album. A classically trained musician in his own right, he understands music from both sides of the glass. Even when he has worked with artists who’ve had production experience, like Paul Simon or Paul McCartney, Ramone says that he contributed a sense of objectivity that the artists found helpful.

Accommodating in his profession as well as in his prose, Ramone has graciously written a book that music fans of any age or education can appreciate. Given his expertise, he could have easily filled these pages with professional terminology related to record production. While he certainly refers to technological aspects and specific equipment associated with his work, he does so without leaving the average reader overwhelmed or confused. Rather, he only mentions something of this sort within the context of recounting a pertinent (and understandable) experience.

Making Records: The Scenes Behind The Music offers an intriguing glimpse into the art of music production, and few careers in this field have rivaled that of Phil Ramone. Now, in addition to albums, concerts, and other live events, Ramone has once again produced a quality work. And this time, finally, his name is on the cover.

While neither a strict memoir nor a technical manual, the book blends elements of the two, usually within the context of representative and applicable anecdotes.

Ramone writes an engaging account of his ascension in the music industry, from working as a studio apprentice to engineering recording sessions and ultimately producing albums and live events. As a result, the reader gains priceless insight on some landmark recordings as well as perspective on the evolution of music production over the last 50 years.

What makes this book such an enjoyable read is the producer’s unassuming way of relating his memories and knowledge. One would suspect that someone as proficient and experienced as Phil Ramone would have, by now, lost all sense of wonder in regard to how music is made. Quite the contrary, while he undoubtedly knows what he’s doing in the studio, he seems just as amazed and inspired by the creative process as any typical fan would feel.

Fans of Billy Joel, in particular, will take pleasure in reading what Ramone recollects about producing many of the Piano Man’s greatest albums. He recounts how certain iconic sound effects were achieved, like the shattering glass that opens “You May Be Right” and the reverberating helicopter propellers that bookend “Goodnight Saigon.” He explains his view on what was lacking in Joel’s first four albums—which he didn’t produce—and why that deficiency resulted in releasing Songs From The Attic. He even divulges how he would humorously blackmail Joel and his band into working whenever they got hungry or distracted.

In sharing his experiences of working with Billy Joel, Barbra Streisand, Frank Sinatra, Ray Charles, and a plethora of others, the consistent factor is how Ramone approached (and still approaches) each project with the artist’s intent foremost in his mind. He astutely notes that his name doesn’t appear on the covers of the albums he produces. Thus, instead of attempting to conform an artist to a certain style or standard, he respects and caters to each artist’s creative goal.

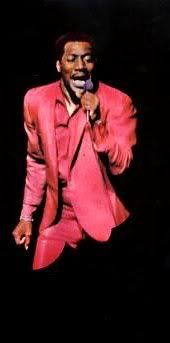

|

| Ramone and Billy Joel, 1986, during sessions for The Bridge |

Accommodating in his profession as well as in his prose, Ramone has graciously written a book that music fans of any age or education can appreciate. Given his expertise, he could have easily filled these pages with professional terminology related to record production. While he certainly refers to technological aspects and specific equipment associated with his work, he does so without leaving the average reader overwhelmed or confused. Rather, he only mentions something of this sort within the context of recounting a pertinent (and understandable) experience.

Making Records: The Scenes Behind The Music offers an intriguing glimpse into the art of music production, and few careers in this field have rivaled that of Phil Ramone. Now, in addition to albums, concerts, and other live events, Ramone has once again produced a quality work. And this time, finally, his name is on the cover.